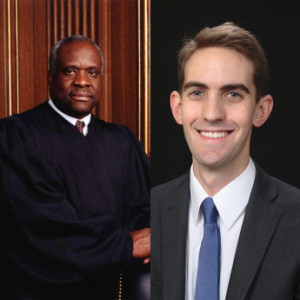

Utah v. Strieff, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) (Thomas, J.).

Response by Edward J. George

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

Concerning Implications for Our Privacy

In Utah v. Strieff,1 the Court reversed Utah’s supreme court, holding that an arrest warrant can attenuate “the connection between the unlawful stop and the evidence seized” incident to arrest.2 The respondent argued that because of the prevalence of outstanding arrest warrants, police would have an incentive to conduct dragnet searches if the Court did not apply the exclusionary rule. The majority, authored by Justice Thomas, disagreed, reasoning that “[s]uch wanton conduct would expose police to civil liability,”3 and that the factors previously identified in Brown v. Illinois4 “take account for the purpose and flagrancy of police misconduct.”5 But Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan, writing separate dissents, disagreed. The two Justices believed that the majority’s decision welcomes police officers to make unconstitutional stops by rewarding officers when they discover an outstanding warrant, admitting into evidence anything found incident to arrest.

This case began when the South Salt Lake City police received an anonymous tip that “narcotics activity” was occurring at a particular residence. Narcotics detective Douglas Fackrell investigated the tip and observed visitors leaving the house a few minutes after arriving. One of the visitors was respondent Edward Strieff. Minutes after Strieff left the home, Fackrell, who the state acknowledged had no reasonable suspicion that Strieff committed any wrongdoing, stopped and questioned Strieff and took his identification, relaying the information to a police dispatcher. The dispatcher informed Fackrell that Strieff had an outstanding arrest warrant for a traffic violation. Fackrell arrested Strieff pursuant to that warrant and discovered a bag of methamphetamine and drug paraphernalia during the search, which was incident to arrest.

Utah charged Strieff with unlawful possession of methamphetamine and drug paraphernalia and Strieff moved to suppress the evidence, arguing that the evidence was obtained from an unlawful investigatory stop. Utah conceded that the stop was illegal but argued that the evidence should not be suppressed because the valid arrest warrant attenuated the connection between the unlawful stop and the discovery of the contraband. The trial court agreed and admitted the evidence. Strieff conditionally pleaded guilty but reserved his right to appeal the trial court’s denial of his suppression motion. Utah’s court of appeals affirmed the conviction, but Utah’s supreme court reversed, finding only a voluntary act of the defendant’s free will sufficiently attenuates the illegal search and the discovery of evidence.

From a doctrinal standpoint, the majority’s opinion is rather boring. The opinion does not purport to break new doctrinal ground; rather, it simply applies the Brown factors and concludes that suppression is unwarranted. Moreover, the opinion does not overturn or substantially revise Wong Sun v. United States;6 rather, it purports to reconcile pre- and post-2000 case law on the “fruit of the poisonous tree,” recognizing that the Court in these cases performed cost-benefit analyses.7 And while others have analyzed Justice Thomas’s opinion,8 none seem to have noted the severe implications of the majority’s opinion for privacy.

Justice Sotomayor was correct in that Utah v. Strieff is a huge win for the police. Justice Thomas’s opinion essentially creates an exception to the exclusionary rule for searches of persons who have outstanding warrants. And given that there are millions of outstanding arrest warrants,9 police have been given an unfortunate incentive to stop individuals without reasonable suspicion.

In the digital age, one’s identity is far more than just a name. Today, it can unlock a trove of information stored in various state and federal law enforcement databases10 that lay bare some of the most intimate details of an individual’s life. The fear is that as law enforcement databases grow, running a name will give the police officer access to information providing a post hoc justification for any police encounter.11

Prior to this decision, the Court had previously held that that “questions concerning a suspect’s identity are a routine and accepted part of many Terry stops,” but with the important caveat that identification cannot be compelled if the request is not “reasonably related to the circumstances justifying the stop.”12 And Utah specifically recognized this requirement by codifying it into law.13

But the Court’s decision in Strieff has essentially permitted law enforcement to circumvent these restrictions. Now we must fear that law enforcement will routinely compel identification in the hope that it will reveal information that justifies a search or an arrest—all while knowing that a stop that yields nothing has a minuscule chance of becoming a civil liability. Given the vast amount of information law enforcement databases contain, it is not hard to imagine a future where “routine ID checks could very well lead to prolonged detention or examination.”14

And this is particularly troubling given what one privacy expert has termed “the color of surveillance.”15 As Justice Sotomayor correctly noted, while this case illustrates that anyone’s dignity can be violated by stops without justification, this type of scrutiny disproportionately affects people of color. The Fourth Amendment protects “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures . . . .”16 And the Court recognizes that “[n]o right is held more sacred, or is more carefully guarded, by the common law, than the right of every individual to the possession and control of his own person . . . .”17 But how do we reconcile these maxims with daily life in a country that allows a large portion of its population to be subjected to routine privacy invasions while courts excuse the violations of their rights?

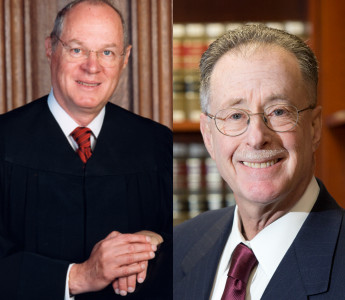

Justice Alito noted in Riley v. California18 that “it would be unfortunate if privacy protection in the 21st century were left primarily to the federal courts using the blunt instrument of the Fourth Amendment.”19 And he is right. It is unfortunate that we have allowed privacy to be left primarily to the federal courts because, as we have just seen, our rights are easily weakened when entrusted to their hands. Perhaps it is time to consider a different method to protect our privacy.

Edward J. George is a rising third-year at Georgetown University Law Center and the Chief Research Assistant for Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology. Edward is currently a Summer Associate at Paul Hastings LLP, and previously served as a law clerk for Senator Al Franken, Ranking Member of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law. Edward attended Syracuse University, where he spent a year studying at the London School of Economics and Political Science, and graduated with a B.A. in Economics.

- Utah v. Strieff, No. 14-1373, slip op. (U.S. June 20, 2016).

- Id. at 10 (majority opinion).

- Id.

- Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1975).

- Strieff, slip op. at 10.

- Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963).

- See Orin Kerr, Opinion Analysis: The Exclusionary Rule Is Weakened But It Still Lives, SCOTUSblog (June 20, 2016), http://www.scotusblog.com/2016/06/opinion-analysis-the-exclusionary-rule-is-weakened-but-it-still-lives/.

- Id.; see also Stephen Saltzburg, Response, Utah v. Strieff: Chipping Away at the Exclusionary Rule, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On The Docket (June 23, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/utah-v-strieff-chipping-away-at-the-exclusionary-rule/.

- See Nick Selby, The Backlog: Misdemeanor Arrest Warrants In The USA, Medium (Oct. 6, 2014), https://medium.com/@nselby/the-backlog-misdemeanor-arrest-warrants-in-the-usa-213145467db2.

- See Press Release, Fed. Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Justice Info. Servs. Div., FBI Announces Full Operational Capability of the Next Generation Identification System (Sept. 15, 204), https://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/fbi-announces-full-operational-capability-of-the-next-generation-identification-system; DHS, 2014 National Network of Fusion Centers Final Report (Jan. 2015), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/2014%20National%20Network%20of%20Fusion%20Centers%20Final%20Report_1.pdf.

- Brief for Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) & Twenty-One Technical Experts And Legal Scholars as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondent, Utah v. Strieff, No.14-1373 (U.S. Jan. 29, 2016).

- Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial Dist. Court of Nev., 542 U.S. 177, 186, 188 (2004).

- Utah Code Ann. § 77-7-15 (2015).

- Brief of Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) & Twenty-One Technical Experts And Legal Scholars as Amici Curiae Of Respondent, Utah v. Strieff, No.14-1373 (U.S. Jan. 29, 2016).

- See Alvaro M. Bedoya, The Color of Surveillance: What an Infamous Abuse of Power Teaches Us About the Modern Spy Era, Slate Magazine (Jan. 18, 2016), http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2016/01/what_the_fbi_s_surveillance_of_martin_luther_king_says_about_modern_spying.html.

- U.S. Const. amend. IV.

- Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 9 (1968) (internal quotation marks omitted).

- Riley v. California, 134 S.Ct. 2473 (2014).

- Id. at 2497 (Alito, J., Concurring).

Recommended Citation:

Edward J. George, Response, Utah v. Strieff: Concerning Implications for Our Privacy, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (June 28, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/utah-v-strieff-concerning-implications-for-our-privacy/.