Encino Motorcars, LLC. v. Navarro, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) (Kennedy, J.).

Response by Alan Morrison

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | Bloomberg | SCOTUSblog

Bringing Deference in for a Tune-Up

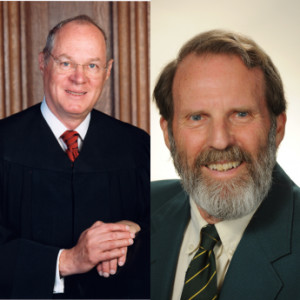

Encino Motorcars v. Navarro1 is a suit by service advisors for an automobile dealer who claim entitlement to overtime pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”), 29 U.S.C. § 207(a)(1). Under that provision, employees must be paid time and a half for overtime hours worked unless there is an applicable exemption.2 In this case, the employer relied on an exemption found in section 213(b)(10)(A) which applies to “any salesman, partsman, or mechanic primarily engaged in selling or servicing of automobiles . . . .” In the end, the majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, did not decide that question, for which Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Samuel Alito, chided the majority. Instead, the Court concluded that the Ninth Circuit gave too much weight to a recent interpretative rule issued by the Department of Labor and remanded the case to that court for its further consideration. Before discussing that ruling, it is worth examining what these service advisors do and how they earn their livings.

When you go to an auto dealer for a routine checkup for your car or for a specific repair, service advisors are the men and women who sit behind a desk who take down your information, keep you informed on the progress of the work being done, and answer your questions at checkout. You can tell they are not mechanics (although they might have been once) because their hands are clean and they often wear collared shirts with the dealer’s name and no grease on them. What you probably don’t know—and this is the reason for this lawsuit—is that service advisors in many dealerships get paid in whole or in part on a commission basis. That system is understandable when they try to sell you a long term service agreement or an extended warranty, but it also applies to “unexpected” work that comes up during the mechanic’s examination of your car.

Suppose, for example, your car is there for a regular 30,000 mile checkup and the mechanic notices that the frapdazzle is on its last legs and should be replaced. He tells the service advisor, who calls you at work to get your permission to replace it. You ask him what he thinks, and he says something like, “well, you might be able to get another six months out of it, but if it goes, your car will stop running on the spot and it could be a lot more to fix it then than now, when the mechanic is already working on car.” How much you ask, and he quotes a price of $603.89 (including tax). You gulp and say, “I guess I should do it now” since you have no way of knowing whether the advice is correct and you can’t even go online to try to find out, let alone ask another shop for its opinion. The one thing that the service advisor has not told you is that he gets a commission for “selling” the extra $603.89 service. And it is that sales commission that gives rise to the employer’s claim that the service advisor is an exempt employee under the salesman provision quoted above. If you are like me—and like the two consumer advocates who specialize in automobiles whom I asked about the practice—you had no idea that your friendly service advisor has more than a little conflict of interest when he responds to your “do I really need this done now” question.

Now for the legal part. As Justice Kennedy’s opinion relates, the statutory exemption itself and the Labor Department’s rules interpreting it over the years have changed. Federal agencies issue two kinds of rules, interpretive and legislative. The former express the opinion of the agency as to the meaning of terms in a statute, whereas the latter establishes standards for applying provisions in the statute. An example of the latter type rule is the Department’s recent decision to amend the requirements for executive, administrative, and professional workers so that it will apply only when they earn at least $47,476 annually for a full-year worker instead of the current $23,660.3 Assuming that the change is valid, the new dollar amount has the same force of law as if it were in the statute. By contrast, if the Department’s interpretation here had been properly issued after due consideration, the courts would not have been bound to the same extent as if the rule were legislative. Put another way, courts give deference to an agency’s understanding of the statutes that it administers, but there are limits to that deference under Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council.4

There is considerable debate on the Court, in academia, and in Congress as to how much deference, if any, should be accorded agency interpretations of the statutes they administer under Chevron. The Court in Encino Motorcars avoided that controversy because it concluded that the Department’s latest statement on the meaning of this exemption was an unexplained shift from its prior view and hence was entitled to no deference.5 Because the court of appeals had given considerable deference to the Department’s understanding, the Supreme Court sent the case back for that court to analyze the exemption without any special weight given to the Department’s understanding of it. All of the Justices agreed that, while the Department was entitled to change its views on the proper meaning of statutory terms, it had the duty to explain why it changed its mind, and the Department failed to do that here.6 The failure here is at least in part explainable (if not justified) by the back and forth history of this interpretative rule, in which lower court decisions from time to time played decisive roles in the process. Moreover, the first stab at deciding whether service advisors were exempt was done without benefit of notice and public comments, which is permitted for interpretative rules,7 but even when permitted, the lack of public input tends to undermine the confidence of courts that the agency has actually taken into account the range of possible views on the meaning of the law. Indeed, in this case, the Department did provide an opportunity for public comment, yet never explained why it was changing not only its prior view, but the view that it had proposed be elevated to the status of an interpretative rule. The bottom line, as Justice Ruth Ginsburg pointed out in her concurrence, is that this decision is nothing new, but simply reinforces the expectation that agencies that change positions should tell the public in advance that they intend to do so (to encourage contrary views) and, at the very least, explain why the prior position is no longer going to be followed.8

The more difficult question is whether the statutory exemption applies to these commission-driven service advisors. The problem is that the exemption was pretty clearly written with employees other than service advisors in mind. Indeed, it is unclear whether significant numbers of service advisors were paid on a commission basis in 1966 when Congress enacted the predecessor of this provision, and it is almost certain that Congress was not aware of the practice then (if now). By contrast, it is common knowledge that the people who sell cars often work evenings and weekends, come and go as they want, and can earn reasonably good (if not better) salaries if they are successful—all of which, taken together, justify the exemption for them. But service advisors are required to be at their desks at specific times, and if they have to work more than 40 hours a week, it is because that is what their employer demands, not to enable them to earn more commissions. Thus, it is hard to see why, as a matter of principle, they should be treated differently from many other service people at the dealership, although, as the majority points out, there is a general exemption for commission-based employees that might apply and on which Encino may be able to rely.9

But as the dissent argues, the applicable statute does specifically exempt “any salesman”—and these service advisors are certainly that in part—“engaged in . . . servicing automobiles”—and they seem to be doing that as well because they are “selling” one form of “service,” both for extended warranty work and the additional service on their cars that customers inevitably purchase.10 The fact that service advisors do not fit within the stated or assumed purposes of this exemption did not overcome what the dissenters thought the plain language required: an exemption.11

In any event, the Court granted cert in Encino Motorcars on the assumption that it would decide the applicability of the auto salesman exemption, but the majority tossed the problem back to the court of appeals. Perhaps that court will decide the case in a way that the issue will go away, and the Supreme Court will not be asked to revisit it. But given the lack of clarity in the law and the fact that there are auto dealerships in every state, the likelihood of inter-circuit conflict make it almost inevitable that the issue will be back, bringing with it several more years of uncertainty on the part of everyone. Perhaps the decision not to decide the merits is the result of the unfilled vacancy on the Court in a case that might well have produced a 4-4 tie.12

- Encino Motorcars, LLC v. Navarro, No. 15-415, slip op. (U.S. June 20, 2016).

- 29 U.S.C. § 207(a)(1).

- Final Rule: Overtime, U.S. Dep’t of Labor (2016), https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime/final2016/ (prior rate contained in notice of proposed rulemaking cited therein).

- Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, 467 U.S. 837 (1984).

- Encino Motorcars, slip op. at 12.

- Id. at 10.

- 5 U.S.C. § 553 (b)(3)(A).

- Encino Motorcars, slip op. at 2 (Ginsburg, J., concurring).

- 29 U.S.C. § 207(i). The companies also objected to the change in positions, claiming that they had relied on the prior rules in setting employee compensation. As Justice Ginsburg observed, 29 U.S.C. § 259 gives employers a defense based on good faith reliance on superseded guidance that would at least protect them for the period until the new rule was announced and perhaps to the date of an adverse Supreme Court decision. Encino Motorcars, slip op. at 2 (Ginsburg, J., concurring).

- Encino Motorcars, slip op. at 2–3 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

- Another recent FLSA case in which the overtime exemption language pushed in one direction, but the purpose of the exemption pushed the other way, is Christopher v. Smithkline Beecham, 132 S. Ct. 2156 (2012). Justice Alito also wrote Christopher, but in that case he found that another salesman exemption at issue there applied even though literally the employee sold nothing, but rather facilitated and promoted sales through other means. Id. at 2174.

- See Encino Motorcars, slip op. at 1 n.1 (Ginsburg, J., concurring) (disagreeing with Justice Thomas’s views on the merits, “sans Chevron”).

Recommended Citation:

Alan Morrison, Response, Encino Motorcars, LLC. v. Navarro: Bringing Deference in for a Tune-Up, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (June 22, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/encino-motorcars-llc-v-navarro-bringing-deference-in-for-a-tune-up.