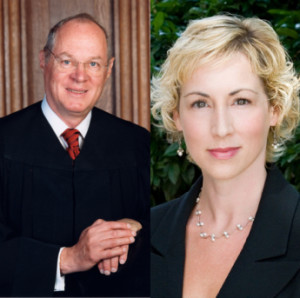

Williams v. Pennsylvania, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) (Kennedy, J.).

Response by Robin Maher

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (Oct. Term 2015)

Slip Opinion | New York Times | SCOTUSblog

Justice Doesn’t Just Happen

The extraordinary facts in Williams v. Pennsylvania1 read like a Hollywood movie script. On one side was the prosecutor-turned-judge who sat in judgment of a defendant whose death sentence he had personally authorized years earlier. On the other side was a poor African-American kid from Philadelphia, sentenced to death at age eighteen for killing the pedophile who had been abusing him since he was thirteen. It would have been a lopsided mismatch, but for the defense lawyers in Williams’ corner. Their diligent efforts found evidence of prosecutorial misconduct so serious that it halted his execution just hours before he was scheduled to die. That is, until the prosecutor-turned-judge voted to reinstate the death sentence he had sought thirty years earlier. It would be hard to believe if it weren’t all true.

Williams’s story began in a poor neighborhood of Philadelphia, where violence and abuse were the norm. His mother was an alcoholic who frequently targeted Williams for horrific beatings and public humiliation. His stepfather was an angry drunk who often beat Williams and his mother. Williams’s traumatic childhood made him an easy target for sexual predators; he was first raped when he was just six years old, the first of many sexual assaults by older men. In 1984, after suffering years of abuse, 18-year-old Williams killed Amos Norwood, a 56-year-old man who had been raping him since the age of 13. Williams was charged with capital murder.

As Philadelphia District Attorney, Ronald Castille had ultimate responsibility for any capital prosecution decision. When his subordinates sought his authorization to seek the death penalty, he approved their request with a handwritten note. At trial, prosecutors told the jury that Williams had killed Norwood simply because Norwood had offered him a ride home. Williams’ defense lawyers, whom he first met the night before the trial began, did no investigation and offered little by way of a defense. Williams was sentenced to death. The jury never learned of his abuse by Norwood nor of his tragic upbringing.

Castille eventually set his sights on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. He stood for election on the backs of the 45 men he had “sent to death row” while district attorney. “Voters,” he explained in a 1993 campaign interview, “care most about crime.”2 Asked what his position on the death penalty would be if elected judge, Castille pointed to the number of defendants sentenced to death under his leadership as District Attorney. One can imagine Castille giving a broad wink as he assured the reporter that voters will “sort of get the hint.”

Twenty-eight years after being sentenced to death, Williams was only days from an execution date when his new lawyers discovered evidence that the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania had kept hidden for decades: prosecutors had secretly rewarded the false testimony of the key witness who testified against Williams at trial.3 They also found notes in the prosecution’s file that proved that the prosecution knew the victim had sexually abused young boys, but had deliberately kept that information from the jury. Almost unnoticed among the boxes of documents was Castille’s handwritten note authorizing death for Williams.

Presented with this newly discovered evidence, a Philadelphia trial court issued a stinging indictment of the prosecution’s conduct and vacated Williams’s death sentence. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania quickly appealed the decision to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, where prosecutors had reason to feel optimistic: Ronald Castille was now Chief Justice.

Williams’s defenders asked Castille to recuse himself from considering the appeal because of his previous involvement in the case. But Castille summarily dismissed the request, refusing even to refer the recusal motion to the full court. When Castille and the rest of Pennsylvania Supreme Court unanimously voted to reinstate Williams’s death sentence, Williams sought review at the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Court agreed to hear the case.

The court of public opinion decided this case before oral arguments were even scheduled. Eight different groups, including former appellate judges, former prosecutors, ethics professors, the American Bar Association, and the American Civil Liberties Union filed amicus briefs arguing that Castille should have recused himself. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania responded that Castille’s decision to seek death for Terry Williams as District Attorney was merely “ministerial” and did not require his recusal. The amici response to their position was deafening in its silence: not a single brief was filed in support.

On June 9, 2016, a divided Supreme Court held that Castille’s failure to recuse himself violated Williams’s Due Process rights. Castille’s authorization to seek the death penalty against Williams amounted to significant, personal involvement in a critical trial decision, and his failure to recuse himself from Williams’s case presented an unconstitutional risk of bias. Importantly, Castille’s participation resulted in “structural error, affecting the State Supreme Court’s whole adjudicatory framework.”4 That meant that the votes of the other justices were irrelevant to the Due Process violation. As the Court explained:

The fact that the interested judge’s vote was not dispositive may mean only that the judge was successful in persuading most members of the court to accept his or her position—an outcome that does not lessen the unfairness to the affected party. A multimember court must not have its guarantee of neutrality undermined, for the appearance of bias demeans the reputation and integrity not just of one jurist, but of the larger institution of which he or she is a part.5

In a sharp rebuke to the Commonwealth’s “ministerial” argument, Justice Kennedy noted that Castille’s authorization was required before the Commonwealth could seek death. “Given the importance of this decision and the profound consequences it carries, a responsible prosecutor would deem it to be a most significant exercise of his or her official discretion,” Justice Kennedy wrote.6 He further observed:

[Castille’s] willingness to take personal responsibility for the death sentences obtained during his tenure as district attorney [during his election campaign] indicate[s] that, in his own view, he played a meaningful role in those sentencing decisions and considered his involvement to be an important duty of his office.7

Even the dissenters, Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito and Thomas, conceded that Castille’s failure to recuse might have been “[in]appropriate”8 and “unwise,”9 but argued that his recusal was not Constitutionally required.

With the remand from the Court, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court now has another opportunity to do right by Terry Williams. And with three new justices and Castille retired, there is every reason to hope that a fair hearing will finally give Williams the justice he deserves.

While much has been written about the Court’s decision, there has been little acknowledgment of the reason this case even reached the Court at all: his lawyers. This case is a victory for the cause of zealous representation—the effective and unyielding defense effort that all criminal defendants deserve in our adversary system but too few receive. It is an essential reminder that justice doesn’t just “happen.” Justice requires good defense lawyers.

Terry Williams’s trial lawyers failed him, as had nearly every adult in his young life before he was sentenced to death. After almost three decades on death row, he had little reason to expect things would ever be different. But his luck changed when the Federal Community Defender Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania took his case. Williams was a dead man walking without the extraordinary dedication and considerable efforts expended by the lawyers, paralegals, investigators, and all the staff in that office who made winning justice for him their collective cause. The decision in Williams has real legal significance, but to me, this case also demonstrates the difference that ethical, dedicated, skilled, and adequately resourced defense lawyers can and must make in our legal system.

When I train defenders who work in other death penalty countries, I try to explain the meaning of “zealous defense” to lawyers who do not work in an adversarial system. I try to describe why it is so important to ensuring the dignity of the individual, and to justice itself. Their often blank faces reveal little understanding of what it means to figuratively throw yourself between your client and his executioner. The idea that an advocate should challenge the government’s case—continuously and assertively—is a remote and somewhat unattractive concept to many foreign lawyers, and sadly, even to many defense lawyers in the United States. But in our legal system, it is the only way to achieve justice for an individual, and to prevent the abuses of government with its enormous advantages of resources and power.

Williams’s lawyers understand this. Their fight for Terry Williams is not over, but the edited script now makes a Hollywood-style happy ending for him more possible than ever.

Author’s Disclosure: I have been working as an assistant federal defender in the Capital Habeas Unit in the Federal Community Defender Office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania since September 30, 2015, two days before certiorari was granted in Williams v. Pennsylvania. The opinions expressed in this article are strictly my own and not those of the Federal Community Defender Office, George Washington University Law School, or anyone else.

- Williams v. Pennsylvania, No. 15-5040, slip. op. (U.S. June 9, 2016).

- Katharine Seelye, Castille Emphasizes Law-and-order Image, Phila. Inquirer (Oct. 21, 1993), http://articles.philly.com/1993-10-21/news/25937931_1_ron-castille-supreme-court-parade.

- The Commonwealth’s key witness, Marc Draper, told Williams’s defenders that he had informed the Commonwealth before trial that Williams’s motive for killing Norwood was the fact that Norwood had been sexually abusing him. According to Draper, the Commonwealth had instructed him to give false testimony that Williams killed Norwood to rob him. Draper also disclosed that the trial prosecutor promised to write a letter to the state parole board on his behalf. At Williams’ trial, the prosecutor had elicited testimony from Draper indicating that his only agreement with the prosecution was to plead guilty in exchange for truthful testimony. No mention was made of the additional promise to write the parole board. See Williams, slip op. at 3.

- Id. at 14.

- Id. at 3.

- Id. at 2.

- Id. at 9–10.

- Id. at 8 (Roberts, C.J., dissenting).

- Id. at 13 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

Recommended Citation:

Robin Maher, Response, Williams v. Pennsylvania: Justice Doesn’t Just Happen, Geo. Wash. L. Rev. On the Docket (June 14, 2016), http://www.gwlr.org/williams-v-pennsylvania-justice-doesnt-just-happen/.